WRIGHT-PATTERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Ohio – Aiming a laser at an aircraft is a federal crime that can net offenders up to five years in jail or cost them a $250,000 fine. Even with this heavy potential penalty, laser strikes have become increasingly more common. According to the FAA, 6,852 such incidents were reported in 2020, compared with 385 in 2006, and so far this year, incidents of “joy lasing” are up 20 percent over last year. Cheap and easily obtained, hand-held lasers used as pointers and cat toys are certainly harmless when used as intended. But when they are aimed at the cockpit of an aircraft, they can temporarily blind the pilot — with possibly deadly consequences.

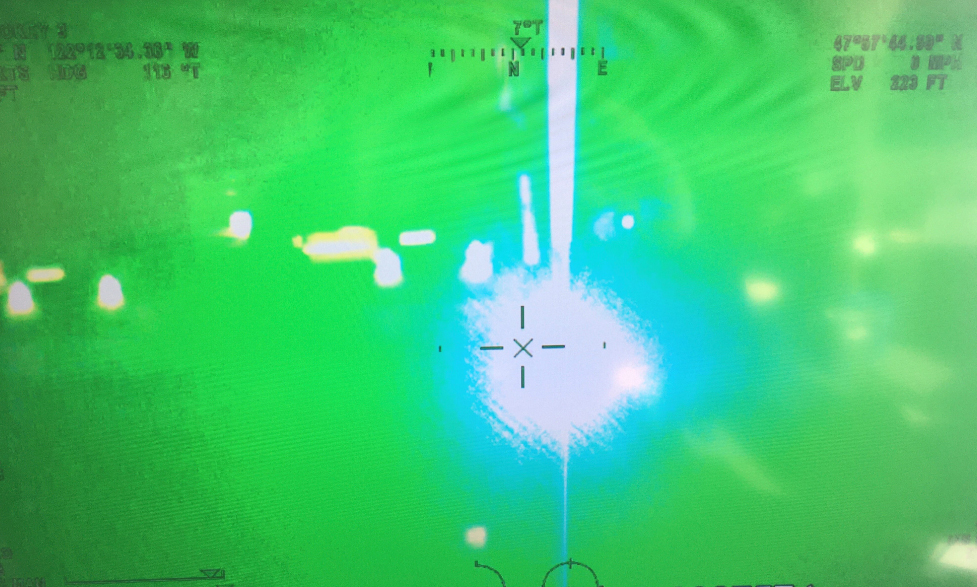

Laser strikes are almost always made at low altitudes when an aircraft is taking off or preparing to land — the two parts of flying that require the most attention from a pilot. Even if the beam of light does not hit the pilot’s eyes directly, it can cause a distraction or even raise an alarm that the plane may have become a target. In addition to the possible adverse effects of these human reactions, slight imperfections in the plane’s windscreen can cause the laser light to spread out, creating a glare that can temporarily obscure all vision inside the cockpit.

Of course, passing a law against any behavior — including pointing a laser at an airplane — seldom puts an end to the behavior. Thus, the best way to avoid disaster from laser strikes is to provide some sort of protection for the pilot. As a result, in recent years several manufacturers have developed laser eye protection (LEP) to meet a growing demand for help from military and law enforcement pilots. But this solution is not without problems of its own.

Most laser eye protection works by filtering out green or red light, the colors most commonly used in handheld lasers. Unfortunately, according to FAA studies and years of pilot experience, this can change the pilot’s ability to accurately read the instrument control panel. A 2019 FAA report suggested that this problem might be fixed by changing the type of lighting in the control panel.

Researchers at the Air Force Research Laboratory recently came up with a better solution, one that was successfully tested on the job by Washington State Patrol pilots.

The Personnel Protection Team in AFRL’s Materials and Manufacturing Directorate, headed by Dr. Matthew Lange, used the cockpit compatibility design software developed for Department of Defense LEP and modified it for commercial use. The commercial version, called CALI (Commercial Aviation Low Intensity) filters out the laser light, but not the light coming from the pilot’s instrument panel. “Simply put,” said Lange, “the lenses maximize protection while minimizing the impact to the cockpit.”

According to Lange, AFRL currently works with the industrial base on all levels of LEP development, production and sustainment, from “cradle to grave.”

“We are involved from the basic research for creating the lenses into how to scale up production at the industrial level,” said Lange. “There are already a handful of manufacturers out there who can make optical grade polycarbonate lenses incorporating the technology used in the CALI system.”

Lange went on to explain that AFRL has been working on laser eye protection for more than 20 years. “When Materials and Manufacturing comes up with a design, the 711th Human Performance Wing tests it and gives us feedback on what needs to be changed,” said Lange. “The expertise that exists within AFRL right now is based on that pedigree.”

Lange stressed the importance of the collaboration between his lab, AFRL’s 711th Human Performance Wing, and private industry to come up with the new dyes and coatings and making sure they were incorporated into the final product. Lange especially acknowledged team members Maggie Lankford, Nicholas Garvin, Gregg Irvin and Everett Rae for their important work in developing this product.

Knowing that its protective lenses would be important outside the Department of Defense, AFRL has spoken with the FAA about using the technology in commercial aviation. “It’s challenging,” said Lange, “because the FAA is not the Department of Defense, so they can’t use all of the technology we have at our disposal here.”

Another part of the problem is that the FAA’s job is primarily to make regulations, not acquire equipment. “So, the FAA is trying to come up with a policy informed by the technology, technology that doesn’t exist in the industrial base because there was no previous demand for it,” said Lange. “There was no demand because there was no rule yet. So, there was this circle that we were having a problem completing.”

Nonetheless, according to Lange, retired team member Bryan Edmonds, a pioneer in the development of LEP, “had been evangelizing LEP to the FAA for over a decade.”

Working with team members, Dan Brewer and Hank Morrow (both also now retired), Edmonds did manage to get the attention of the FAA. As a result, the FAA knew who to ask when it was ready for its own LEP plan.

Lange explained that things finally changed in 2020 when collaboration with the FAA gained some momentum. “As a result of this partnership,” he said, “when the Washington State Patrol folks called, we had something ready.

“During the riots in 2020, law enforcement reached out to the community and asked who knows anything about laser eye protection,” explained Lange. “The 711th Human Performance Wing and the Naval Medical Research Unit Dayton [also at Wright-Patterson] all juggled a number of briefings about what is available in the industrial base, effects on human factors, etc. Most of the eye protection available to the police was the standard issue, non-CALI type.”

However, one particular group of aviators in Washington State tried the CALI products and decided they “were head and shoulders above the others.”

One of those aviators was Trooper Pilot/Tactical Flight Officer Camron Iverson of the Washington State Patrol. “We had some new laser glasses that we were supposed to test out that the Air Force had developed” said Iverson. “I know we were the first ones to test them.”

Iverson explained that the aircraft he flies gets around 20 to 25 laser strikes a year. “We’ve been finding about 80 percent of the violators. We can spot the source of the laser light, using an infrared camera, and then walk other law enforcement officers to the address or location and actually apprehend these people.”

When asked why anyone would aim a laser at an airplane, Iverson answered that he has heard a lot of different excuses. “Sometimes it’s just kids goofing around,” he said. One violator responded by saying, “I thought it was a police officer so I flashed my light at him to make him go away.”

Iverson has personally experienced a laser strike from inside the police aircraft. “For about an hour I was having ‘white spot,’” he said. At night, the eye’s pupil is opened wide, making flash blindness greater and longer lasting.

Using the CALI lenses will prevent such problems. “I’ve been wearing them just about every flight that I go on, just in case,” said Iverson. “They’re comfortable to wear and you don’t really notice that they’re on you. That’s my experience.”

Unlike the non-CALI lenses, color perception is minimally affected.

“It doesn’t distort colors too tremendously bad,” said Iverson. “I think the biggest distortion that we see is that it does darken up white, making it look more yellowish. But your reds and blues — even your greens — that are displayed on the instrument panel screen still look red, blue and green.”

The best assessment might be the one from Washington State Police pilot, Jeffrey Hatteberg, who wrote in an email to Lange and other team members: “Thank you all again for the assistance and opportunity to test out the laser glasses, they have been a huge success with our pilots. Just last night we had another two laser incidents and the glasses worked great!”

Flight Officer Camron Iverson of the Washington State Patrol tested laser protection lenses formulated at AFRL’s Materials and Manufacturing Directorate. (Courtesy photo)

When a laser beam strikes a windshield, it often diffuses, making the windshield temporarily opaque. (Courtesy photo)