WRIGHT-PATTERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Ohio (AFRL) – Ensuring a steady supply of technical and scientific expertise for American industry and innovation has been a national priority since about 1957 when the Soviet Union launched its first Sputnik. Today, however, with the increasingly rapid pace of high technology, the need to attract young people to the field of advanced technical manufacturing has become even more critical. To meet that need, the Air Force Research Laboratory recently tasked NextFlex with finding ways to attract students who might not otherwise consider such a career path.

Formed in 2015, NextFlex is a Manufacturing Innovation Institute established by the Department of Defense’s Manufacturing Technology Program. AFRL’s Materials and Manufacturing Directorate at Wright-Patterson has partnered with NextFlex through a cooperative agreement to ensure this specialized workforce development (WFD) is carried out through the mission of the institute.

Manufacturing innovation institutes are partnerships formed by the Defense Department with industry and academia to help accelerate the development of promising technologies that are useful to both defense and commercial applications.

NextFlex focuses on the development of flexible hybrid electronics (FHE). In addition to working on developing FHE manufacturing capabilities, another of NextFlex’s goals is to develop an education and workforce development (EWD) program.

According to Emily McGrath, NextFlex’s Workforce Development Director, part of the consortium’s mandate as a manufacturing innovation institute is “to ensure the creation of a skilled pipeline of STEM talent needed to drive technology progress.” The talent in question is not necessarily in research and development, but in the manufacturing of high technology products.

McGrath said NextFlex has developed a portfolio of education and training programs to meet this goal. One of those programs, FlexFactor, is showing especially great results and impact.

“Our most mature program is FlexFactor,” said McGrath, “an outreach and recruitment program designed to raise K-12 student awareness about flexible hybrid electronics, advanced manufacturing career pathways, and the role of the Department of Defense in technology development.”

Flexible hybrid electronics are conductive circuits that are printed on a flexible substrate, for example, a strip of plastic. They are especially useful for such applications as wearable medical sensors.

The FlexFactor educational program is designed to be layered over an existing curriculum. It challenges small teams of students to identify a real-world problem, think of an advanced hardware product that might solve that problem, and then create a business model around their solution.

The program usually runs five weeks and includes a tour of an industry facility, a college campus, and mentored workshops. To wrap up the program, each team pitches its product ideas to a panel of experts — a process referred to by participants as the “shark tank.”

“Colleges adopt and run FlexFactor for local high school students in their service area as a means of engaging students with STEM pathways in higher education,” explained McGrath. “So although the participants are all in high school, the teams represent their colleges (not their high schools) in the finals, because we work with the colleges, not the high schools, to run the program.”

In the Fall 2016, NextFlex launched its pilot FlexFactor program in San Jose, California. The following year, more schools were added to the program. In 2019, AFRL connected NextFlex with Sinclair Community College in Dayton, Ohio.

According to Julie Huckaba, FlexFactor program manager at Sinclair, one problem to overcome is to create enthusiasm among the students for advanced manufacturing careers. Often they feel coerced into doing something that is outside their field of interest. They mistakenly believe that only people with a technical mindset already in place, for example a computer “nerd,” would get anything from this program.

“The FlexFactor iteration that Sinclair held with Jefferson Township High School,” explained Huckaba, “was in a sociology elective class. Instead of typical problem ideas around STEM, these students looked to solve the problems of police brutality, homelessness, sustainability, and waste and recycling. The structure of the program allowed the student groups to address problems that mattered to them while also giving them the ability to conceptualize a very technical product to solve those problems.”

By visiting facilities where advanced manufacturing takes place, students see that today’s factories don’t look like the ones they may have seen in photos in their history books.

As an example, Huckaba points out that current FlexFactor students from Piqua High School had the opportunity to visit Hartzell Propellers, a modern manufacturing facility. “Hartzell Propellers has been in business [in Piqua] since 1914,” she said, “and the tour they provided showcased their clean, well-lit facility that uses state-of-the-art manufacturing processes. The students truly enjoyed visiting and learning about a facility that is in their hometown.”

One of the goals of the program is to demonstrate to the students that a career in high technology does not necessarily require a four-year college degree.

“Sinclair offers multiple associate degree pathways as well as short- and long-term certificate coursework that can lead to industry-recognized credentials with excellent earning potential,” said Huckaba. She pointed out that computer numerical control (CNC) machinists in the Dayton area can make a starting wage of between $20 and $30 per hour, and a quality control technician can make up to $24 per hour.

“Sinclair offers a one-year certificate program that prepares students to take the Certified Quality Technician exam from the American Society for Quality,” added Huckaba.

Although the main thrust of the program deals with manufacturing careers, research and development are critical parts of the manufacturing technology process. Thus, FlexFactor also serves as a pathway to a range of manufacturing careers from technicians to engineers. That is one of the reasons AFRL wanted to develop a local workforce for advanced technical manufacturing.

“Part of what we are doing is finding and ‘harvesting’ talent by drawing in high school students and showing them some of the opportunities that a career in science and engineering can create,” said Giorgio Bazzan, AFRL Program Manager and Government Chief Technology Officer of NextFlex.

To enhance its role in the program, AFRL has conducted virtual tours of its laboratories, giving students the opportunity to see what scientists and engineers do there. As part of the tour, students hear personal stories from various research scientists about how early exposure to science and engineering affected their career path.

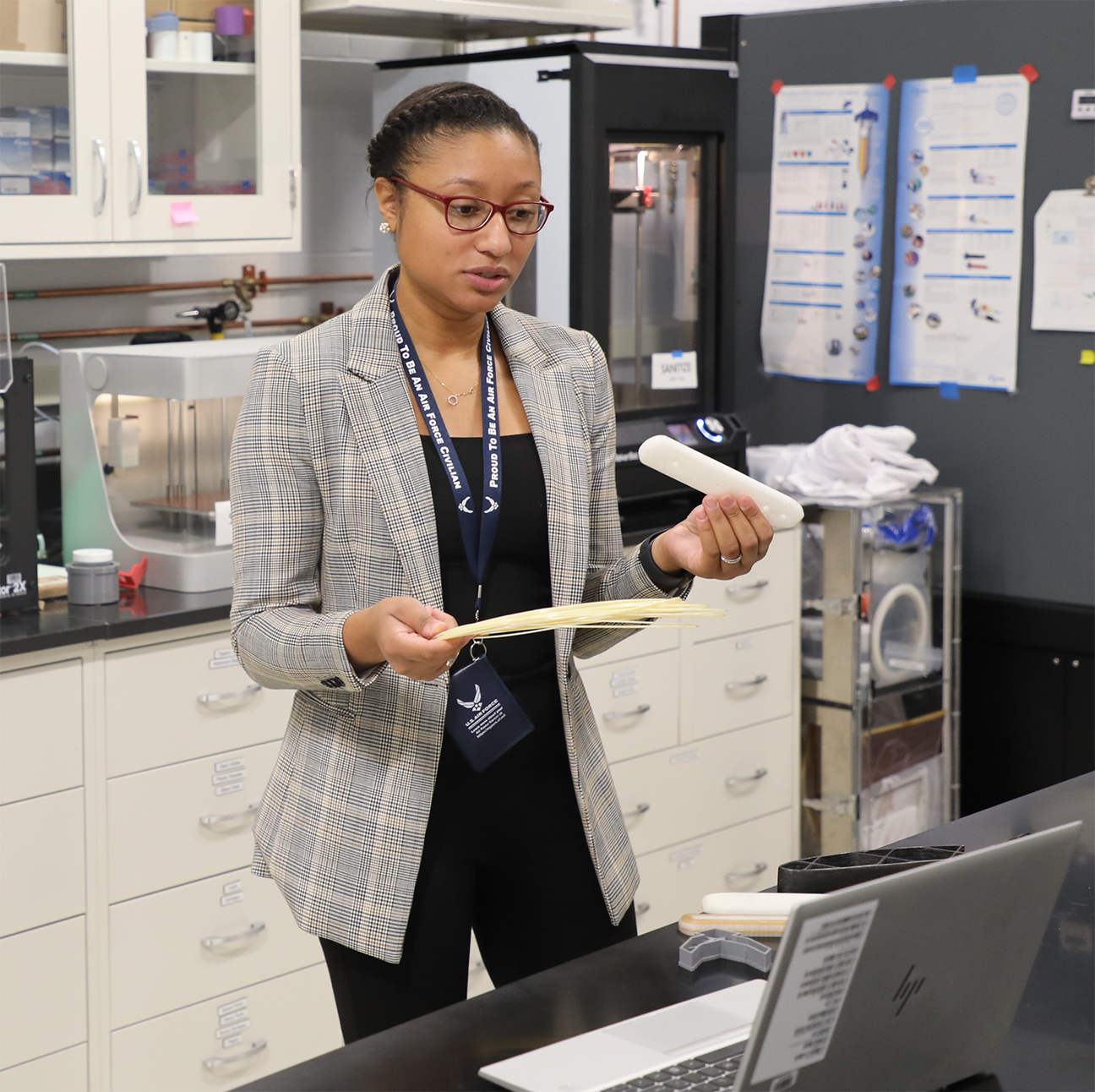

During a recent tour — which was virtual because of the pandemic — students from Shawnee High School and the Greene County Career Center met five research scientists who work at the Materials and Manufacturing Directorate’s facility at Wright-Patterson. One of the scientists was civilian chemical engineer Dr. Roneisha Haney, a newly minted PhD. Haney specializes in finding ways to use additive manufacturing (that is, 3D printing) to produce lightweight, but strong, aircraft components.

Like the other researchers presenting that day, Haney stressed the importance of minimizing student debt in college. “Pay attention to how much debt you are accumulating in getting your degree,” she advised. “There’s a lot of funding out there.”

Haney, who has been employed at the research lab for two months, said she also worked several jobs to help pay her post-grad tuition, including restaurant work, chemistry labs, and driving for Uber.

In addition to helping start the FlexFactor program and conducting tours, researchers from AFRL have offered to mentor local students as they work through the five-week course.

Dr. Roneisha Haney shows the students lightweight aircraft components made by additive manufacturing. The presentation was virtual because of COVID-19 restrictions. (U.S. Air Force photo/Wesley Deer)